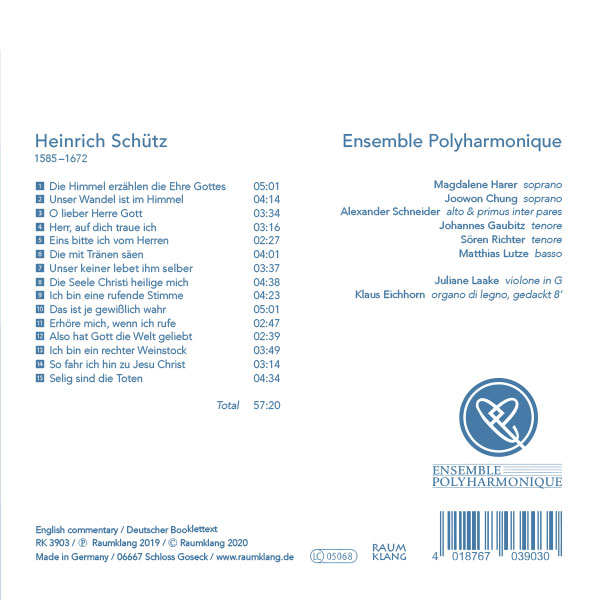

The musical universe in a nutshell |

or the theory of gravity according to Heinrich Schütz

When inedible nuts are found hanging from their bushes the usual culpit is the so-called hazelnut-drilling-insect, the curulio nucum. These are easily identifiable by their thin needle beak, topped off by their pincer-like chewing accoutrements. By means of this equipment the female eats holes through the shells of the incipient hazelnuts and places, cuckoo fashion, her own eggs therein. In the fullnes of time the actual pests evolve from these eggs, in the nourishing kernel and leave a hollow, empty nut behind them, which ripens prematurely and falls off. The larvae leave the hollow nut behind, burying themselfs in the topsoil and hibernating there in their cocoon. When they have achieved maturity the parasites fly back to the hazelnut bush, devouring the nuts and leaves.

Irrespective of how knowledgeable he was in biology or pest-control, Heinrich Schütz or to use his „nom de plume“ Sagittarius, in his preface to Geistliche Chor-Music 1648, uses this telling metaphor to underline the extent of the compositional mastery of his collection of motets. In his Geistlicher Chor-Music 1648 Schütz is concerned with nothing less than the „nutritious kernel“ of the music. This metaphor is what he is inferring in his legendary preface to the famous motet collection. He is fully conscious of his artistic authority, respected throughout Europe. He speaks thus of the „necessary Requisita“ of the art of musical compostion and enumerates various techniques of counterpoint. But then he wags his schoolmasterly finger and warns: „if these Requistita (necessary requirements) are missing, not one single composition can succeed, at least not for the ears of the conoscenti able to perceive the heavenly harmonies therein, and the whole can at best be described as a hollowed out, inedible nut!“ This is clearly and powerfully expressed, with the certainty of one who, as composeer and teacher, had a decisive influence on the development of music in central Europe.

But what exactly did Heinrich Schütz mean with his simile of the „inedible nut“? Had he become a conservative composer in his old age, who placed the arrows of the avant-garde, which he himself had for years let fly back into the quiver of tradition and dry textbook theory? A little: Yes, but also quite unequivocally No! Etymology provides an answer, in particular with recourse to the„Brüder Grimm“ dictionary. Here the German word „taub“ (taube Nüsse=inedible nuts) is defined as something wherein nothing can be felt or peceived: spoiled, without content, vacant,barren, hollow, bleak, worthless and void. Moreover, when something is „taub“ then it´s entirely lacking in feeling. In his preface and in the motets themselves Schütz is searching for the „sine qua non“, the preconditions whereby music can ripen like fruit, and evidently without producing any „inedible nuts“ or empty shells. He wishes to ensure that sensations, feelings and perceptions are all clearly sensed, felt and perceived in his music, which is why he tackles this literally fundamental concern in his motets. He isn’t concerned with turning his back on the futuristic arrows of musical progress but with a well- ordered flightpath: in evidence already in his first extended cycle of 1619, the Psalmen Davids (the Psalms of David), where he warns of chaos in the musical universe. If these modern psalms are performed without understanding, then there is danger that, in the worst case scenario a “Battaglia di Mosche” (War of the Flies) may ensue, contrary to the author´s intentions. If you try for one moment to follow how and why the fly flies at it does, then you will immediately comprehend what Schütz is getting at. This great document, which unites Italian avant- garde with central German tradition brings with it the inherent danger of complete confusion, if not approached with the right knowledge or “science”. However, throughout his works, Schütz points out that there is a counterweight. Repeatedly he employs the term „teutschen gravitet” (German gravitas), which, particulary in his Dresdner Hofkapelle (Dresden court church), “can be heard in bynear full flower, approaching perfection”. Self-evidently one can perceive a certain element of national self-appreciation here! Schütz mentions this „gravitet” in contradistinction to the Italian colleagues at the Dresden court, „thrice younger and to cap it all, castrated”, musicians such as Peranda.

Schütz observes with displeasure how these new arrivals, adjusting the old traditions to their somewhat common new manner, albeit without good reason („mit schlechtem grunde”, a term coined from Natural Sciences), denounced for lacking the compositional suit of armour possessed by Schütz! If this sounds conservative, that´s because it is – in the original meaning of the world. Schütz intention was to conserve and preserve. Even when brand-new Schütz´s Geistliche Chor-Music 1648 wasn’t modern. The sacred Concerti not uninfluenced by the spirit of the new form of opera had already left the Motets far behind. But that was hardly the point. Schütz was perfectly capable of composing concerti as he showed in 1650 so impressively with his Symphoniae sacrae. The Geistliche Chor-Music aims elsewhere and has a completely different rôle in the oeuvre of Schütz. Consequently, typical of Schütz, who was thinking in categories of Gesamtwerk and his legacy, and who, with his cycles, over and over again attempted to present a sum-total of his own achievements, calculating that the Geistliche Chor-Music should be published first, as a basis, a point of departure and a foundation for the Symphoniae sacrae III, his opus magnum (masterpiece) which appeared two years later.

To understand the 1648 motets it is important to know that they were conceived in terms of a legacy. From 1650 onwards we can observe that Schütz was progressively developing a sense of his own place in musical history. In 1651 he spoke in an extensive review that he wanted to correct and complete the works he had begun in his youth, and to have them printed as a memorial. He was concerned that the good reputation he had earned earlier should be maintained and strengthened in his latter days. Memorial and self-assertion – these were new priorities, which the concept of the transience of human life lowered like a curtain over his works and the need for his compositions to live posthumously. Schütz´s oeuvre, melded with his thoughts about the coming generation of new composers as whose father he wished to be accepted. After all he was already more than 60 years old and he had made great play, pronouncing “The lengths of our life is threescore years and ten”. His concern that he did not have long to live was justified, and he had repeatedly complained of physical weaknesses. Already in 1651 Schütz noticed that his face was thinning out and that his vitality was completely disappearing. What was the legacy which he felt to be threatened?

Here we turn full circle and find ourselves once again in the preface to the Geistliche Chor-Music and his emphasis on the necessary „Requisita”, the pre-requirements for musical composition. How concerned Schütz was that the seriousness (Gravität) of musical composition was undervalued, can be seen by the fact that in the afore-mentioned preface he developed an all-encompassing theory of music from the treatise of a musical friend. Without any doubt he was referring to the work of his favourite pupil, Christoph Bernhard, which we know today as the “Treatise of Composition by Heinrich Schütz augmented by his pupil Christoph Bernhard”. Here we have to slightly digress, because that which the “greatly honoured miraculous German pair Schütz and Bernhard” achieved, as described in an ode by the composer and poet Constantin Christian Dedekind is simply too far-reaching not to digress! Schütz wrote a collection of works, a foundation intended to be a serious order-enhancing source of inspiration for future generations. He announces in his preface the theoretical shoring up of his compositions, to be completed soon thereafter by Christoph Bernhard. In 1663, through the mediation of his friend, Matthias Weckmann, Bernhard was appointed director of music at the Jacobikirche in Hamburg. For a few years, together with Dietrich Buxtehude of the „Norddeutsche Schule” Weckmann left traces in Hamburg. In 1674 he was back in Dresden where he was active for a further 14 years as conductor, whereafter, highly esteemed he went into retirement before he died in 1692. 40 years later we can find in the famous Musicalisches Lexicon by Johann Gottfried Walter the remark that Bernhard´s original manuscript is now in the hands of the „Hochfürstl. Sachsen-Gothische Capell-Meister, Herr Gottfried Heinrich Stöltzel”, but that copies thereof are abundant, in „many hands”. He who wishes to pursue a Sherlock-Holmes musical line of enquiry, can discover to whom these “many hands” belonged: they were „mitteldeutsche” hands, in the close vicinity of Johann Sebastian Bach.The legacy of Schütz, his „Gravitätstheorie” and his environmentally protective campaign against “inedible, hollow nuts”, mediated by his pupil Christoph Bernhard, found a decisive place in the history of music of the late 17th and eighteenth centuries. It is hardly possible to imagine a more complete preservation of Schütz´s legacy. But that all came far later on. Back to 1648. We should perceive, taking note of Schütz´s own pronouncements, and in conjunction with his entire life´s work, the 29 motets as a unified composition. There we feel the „Gravitas”, as a centre of energy, the creative interpretations of the sacred texts in unendingly novel avenues of sound. It´s not a matter of either/or, but of enjoyment and content, which results from the Italian madrigal style being combined with an advanced compositional technique, so that we hear both the decorative focus on single words and also delve ever deeper to the spiritual and sacred kernel of meaning. In the end Schütz´s focus was the splicing and melding together of two genres, which he achieved with consumate success. He valued the tendrils, garlands and ramifications of the Italian style, in all their modernity, which he had done all his life, still in 1650. But this was only so if there was a properly constructed foundation for the entire edifice, when fundamental principals were observed and when, so to speak, the hazelnuts not only glimmered in all their beauty but also nourished his hopes for the future. Furthermore. Schütz integrated quite specifically the Italian style into his Geistliche Chor-Music 1648: No.27„The Angel spoke to the shepherds” originals from „Angelus ad Pastores ait” by Andrea Gabrieli. This could not have been expressed with greater subtlety and clarity.

Conclusion

When the above-mentioned thoughts about the „Gravitas” on one hand and the highly decorative Italian style on the other are followed through, then on reflection the Geistliche Chor-Music 1648 contains a valuable message for us today and for the future. No more thinking in dichotomies.We must resist the longing to define the world in clearly defined categories. This collection of works represents an attempt to think in the interstices, the hyphens and productive combining of disparate elements. Yes, Schütz speaks of „Gravitas” and means thereby a national musical identity, not exclusively but as reassurance of one´s own musical world, whence without fear or trepidation new, modern and foreign elements can be assimilated. Regional or national identity with Schütz aren´t contradictory, nor are tradition and modernity mutually exclusive. We only have to ensure that the energies balance one another, that „Gravitas” prevails, guaranteeing order and giving orientation, enabling unrestricted development. Especially because he is sure of himself, Schütz is able propagates all this, a culture of permeability and openness.

Dr. Oliver Geisler – Translation: Professor Jonathan Alder, May 2020