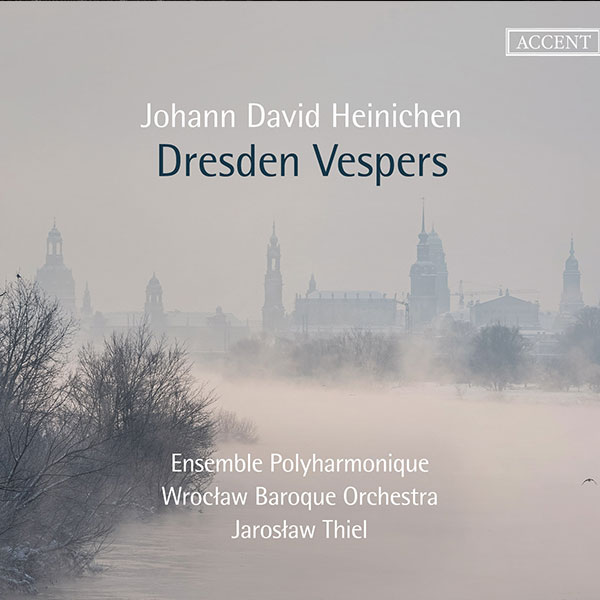

A Protestant Pastor’s Son and a Catholic Saint –

Johann David Heinichen’s Music

for the Feast of St Francis Xavier

by Gerhard Poppe

How did a Protestant pastor’s son come to compose and perform music in honour of a Catholic saint, more precisely, in honour of the 16th century founder of the Catholic World Mission? Such an event occurred in the 1720s at the Saxon-Polish court in Dresden, at a time when conflicts between the confessions had only been provisionally stilled, and tended to flare up whenever the opportunity arose. An introduction to the music recorded on this CD can therefore not be limited to the usual “life and work” format; the compositions, recorded here for the first time, reflect not only their musical, historical and personal constellations, but also the confessional and political situation of the time. Their (pre)history stems from several origins, entwined in a web of internal and external conditions. Johann David Heinichen was born on the 17th of April 1683 in Krössuln, a small village in the Duchy of Saxony-Weissenfels, the son of the local pastor David Heinichen (1652-1719). His musical talent revealed itself at an early age, and he appears to have received appropriate tuition from members of his father’s circle and at the school in nearby Teuchern. As a boy, his father had attended St Thomas School in Leipzig, making it a natural progression to send his son there as well. The young Heinichen went to Leipzig in 1696 and enjoyed the instruction of the Thomaskantors Johann Schelle (1648-1701) and Johann Kuhnau (1660-1722) – apparently so successfully that he was soon teaching composition to his fellow pupils himself. In 1702 Heinichen enrolled at the University of Leipzig to study law, at the same time participating in the two Collegia Musica. Add to this the opera, which played annually from 1693 to 1720 at the New Year’s, Easter and Michaelis fairs, often employing students as performers, and the picture of the old university city – even before Johann Sebastian Bach’s (1685-1750) appointment as Thomaskantor in 1723 – emerges as an extraordinarily auspicious breeding ground for musical talent. Many musicians who later held leading positions throughout Europe acquired their first success in early 18th century Leipzig. In 1705, Heinichen applied unsuccessfully to succeed Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) as director of music at Leipzig’s New Church; instead, he composed several operas and sacred works. In the following years, further opera commissions took him to Weißenfels, Naumburg and Zeitz; in addition, he worked temporarily as a lawyer. In 1710 he accepted the offer of a Zeitz court official to travel to Italy. There Heinichen spent most of his time in Venice, composing cantatas and other works including two successful operas, and establishing contacts both with fellow musicians and members of the aristocracy. Through these connections, Heinichen came to the attention of the Saxon Elector Frederick Augustus (1696-1763, known from 1733 as Frederick Augustus II Elector of Saxony, and Augustus III King of Poland), who visited the lagoon city several times on his grand tour. He engaged Heinichen as the Royal-Polish and Electoral-Saxon Kapellmeister in Dresden with effect of the 1st of August 1716, alongside Kapellmeister Johann Christoph Schmidt (1664-1728) who had held the office since 1697. In the run-up to the marriage of the Prince-Elector to Archduchess Maria Josepha (1699-1757), Antonio Lotti (1667-1740) was employed for two years as a further Kapellmeister. The composition and performance of the festive operas for the Elector’s wedding in September 1719 was reserved for Lotti, with Heinichen providing three serenatas. Originally, another grand opera was planned for the 1720 carnival, the commission to compose Flavio Crispo going to Heinichen, but at a rehearsal the castrato Francesco Bernardi (known as Senesino, 1686-1758) tore up the part of his colleague Matteo Berselli (dates unknown but traceable from 1708 to 1721) and threw it at the Kapellmeister’s feet. Despite an immediate reconciliation, King Augustus II (1670-1733, better known as Augustus the Strong), who was in Warsaw at the time, took the incident as an opportunity to dismiss the expensive singers, which in effect meant the end of Italian opera in Dresden for the time being. The scandal remained a lasting memory of contemporaries, the story still being recounted decades later. For Heinichen, the dismissal of the Italian singers and (temporary) closure of the opera also put an end to his field of work. A change of roles would be difficult, Johann Christoph Schmidt was already responsible for (the by now rather modest) music in the Protestant court chapel, and the court concertmaster Jean-Baptiste Woulmyer (also Volumier, c. 1678-1728) and his deputy Johann Georg Pisendel (1687-1755) took care of the instrumental music. On the initiative of the Electoral couple, Heinichen in the years leading up to his death on the 16th of July 1729 instead became responsible for Catholic church music. This had certainly not been the plan at the time of his engagement in Venice, therefore, the question arises: how did it come about?

The starting point of this story was Elector Frederick Augustus I’s change of confession, converting to Catholicism in 1697 in order to be elected King of Poland. In accordance with the religious law of the Peace of Westphalia (1648), this step only applied to his person; nothing changed in the confessional status of Electoral Saxony. Nevertheless, the arising situation offered plenty of potential conflict. For a time, the Saxon Elector lost the Polish Crown to his Swedish-backed rival Stanisław I Leszczyński (1677-1766) only regaining it in 1709 in alliance with Russia. In order to obtain the Pope’s support for his return to the Polish throne, he had the old opera house at the Taschenberg converted into the first Catholic court church after the Reformation in 1708. A small music ensemble was established at the church in the autumn of 1709, made up of Bohemian choristers and musicians subordinate to the clergy. It was responsible for the (initially low scale) music in the Catholic services. The King had great plans for Elector Fredrick Augustus, sending him in 1711 on a grand tour of the most important countries in Europe. In November 1712, on the insistence of his father, the sixteen-year-old converted to Catholicism in Bologna; though this remained a secret until October 1717. After the announcement, Augustus was able to seek a marriage alliance with the House of Habsburg in order to secure favourable circumstances for his son’s claim to the Imperial Crown. On the 20th of August 1719 the Prince-Elector of Saxony was married in Vienna to Archduchess Maria Josepha (1699-1757), the daughter of Emperor Joseph I (1678-1711). The couple subsequently went to Dresden, where – as already mentioned – their wedding was celebrated with incomparable extravagance. Afterwards, the Electoral couple were given their own court residence, and the Electoral Princess in particular took on the role of patroness to the small and still oppressed Catholic community. Based upon her experiences at the Viennese Imperial court, she placed great importance on supporting and promoting liturgical music along the same lines. After the end of the opera, there was – to put it in modern terms – “spare capacity” for this at the court chapel, and the Electoral couple knew exactly how to use it. In addition to Heinichen, they employed “compositeur de la musique italienne” Giovanni Alberto Ristori (1692-1753) and the Bohemian double bass player Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679-1745), both highly experienced composers. They composed their own, completely new liturgical repertoire or adapted works by other masters for use in Dresden. From Pentecost 1721 onwards, the court chapel increasingly took over the performance of music for the services in the (old) Catholic court church, while the court church Ensemble took on other tasks. These sometimes overlapping obligations produced the golden years of music at the Catholic court church of Dresden, with compositional “signatories” as diverse as Heinichen, Ristori and Zelenka. Though on the other hand, a paradoxical situation arose. Until the death of Augustus the Strong, Protestant court services continued to exist and claimed precedence in terms of protocol, despite the now rather modest musical forces, meaning that liturgical specifications and court ceremony time and again had to be reconciled with one another. One of the striking features of worship and thus also of the music in the Dresden court church was the veneration of St. Francis Xavier (Francisco de Gassu y Javier, 1506-1552) one of the founding members of the Jesuit Order, confirmed by Pope Paul III (1468-1549) in 1540. From 1542 until his death he led an extensive mission into Asia, from India to Japan. Together with the founder of the order, Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), he was beatified in 1619 and canonised in 1622; his veneration quickly spread widely in Catholic Europe, not least because of his letters containing vivid accounts of his missionary work. The Jesuits at the Dresden court church celebrated his feast as early as 1710, and Princess Maria Josepha after her arrival chose the saint to be patron of the Catholic House of Wettin, resulting in the regional upgrade of the Saint’s day (3rd December) to a high feast, with the status of an octave, i.e. celebrated for a whole week.

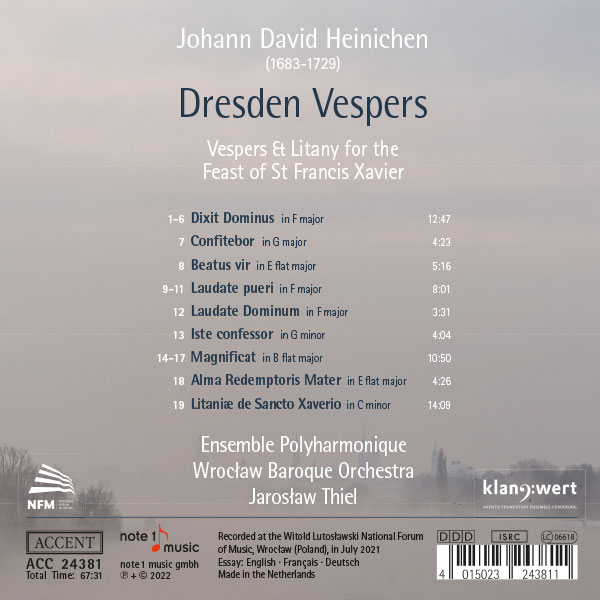

The feast of St. Francis Xavier in Dresden included a solemn mass in the morning and vespers in the afternoon. The texts, which were performed with figural music, did not differ from those of other comparable feasts. In the vespers, the five psalms of the “De confessore non pontifice” (for a confessor who is not a bishop) form were followed by the hymn Iste confessor (which in Dresden consisted of only three verses), the Magnificat and a Marian antiphon according to the liturgical season – in this case the Alma redemptoris mater. Heinichen composed a total of 30 psalms, eight Magnificat settings, eight different vesper hymns and five Marian antiphons in the 1720s, making it possible for the present recording to select from an existing fund in accordance with liturgical specifications. In the case of compositions with dated autographs, the recording was limited to the years 1721 to 1724, so that here we have music for vespers that could have been heard in 1724 on the feast of St Francis Xavier. Conversely, once composed, pieces could be reused at any time on other occasions according to liturgical guidelines in a kind of “modular system”. The extent to which figural music was supplemented by monophonic versicles, readings, antiphons and collects in Dresden at the time is not clear from surviving sources. In view of the time allocated for the entire vespers, and the length of the psalm texts to be set, the composer had to be brief – with the exception of the Dixit Dominus and the Magnificat, for which somewhat more time was available. Heinichen met these demands with a concentrated compositional style that enabled him to create clear and uniform musical images, only exceptionally leaving room for subtleties in text interpretation. This also applies to the hymn Iste confessor, which stands out from the rest of the sequence with its stile antico style, without an independent role for the instruments. As the court church of Dresden celebrated the feast of St. Francis Xavier with an octave, there was a devotion every afternoon for a whole week, centred on the Litaniae de Sancto Xaverio, performed with figural music. The court church chronicles mention this for the first time in 1721. In the following years the practice stabilised, the corresponding music being fom the outset a task for the royal chapel, with several new compositions being written in quick succession. The text comes from the Jesuit order and is modelled on the Litany of Loreto which means a musical realisation offers the same difficulties as the composition of litanies in stile concertato in general. On the other hand, there were no musical models for the realisation of this text. Heinichen’s first Litaniae de Sancto Xaverio composed in 1724 (another composition followed in 1726) thus belongs to the festive context of the year. Together with the works of Ristori and Zelenka, Heinichen’s Litaniae de Xaverius remained part of the repertoire until after the mid-18th century, only then being replaced by new compositions. According to current knowledge, all settings of this text belong to the “unique characteristics” of music at the court church of Dresden.